It is my contention here that among a new era of male voices within rap music new masculine possibilities are emerging. These emerging masculinities are not in there totality progressive. In other words they do not in full seek to deconstruct gender norms, reject misogyny, masculine violence, or homophobia. However, black male rappers are choosing different ways to navigate the complicated nature of black masculinity, given the power of the masculine subject and the lack of value placed on the black body in American society. For the most part they are bringing to the forefront some of the contradictions within the black masculine subject that the “bad man” character, exemplified in the gangsta rap veneer, is supposed to cloud from view. In other words, artists practicing in emerging black masculinities are more likely to engage with the grey areas of their masculine subjectivities. In concluding her book Quinn suggest the possibility of such a shift away from commercialized gangsterism, writing that, “Gangsta rap gave expressive shape to a period in which political protest declined sharply. But now that the pendulum as swung so far across, it is time for counter-energies to begin amassing” (Quinn 192). It is my intention here to articulate some of the counter-energies that may be amassing especially as it relates to how black men are constructing black masculine subjectivity.

First, emerging artists are calling attention to the ways in which the black masculine gangsta subjectivity is constructed and not the default black masculine subject position. Chicago rapper, Lupe Fiasco does just this on his insightful “Daydreamin’ ” on which Philadelphia crooner Jill Scott is also featured. Mocking the pop-gangster posturing, violence, and the use of women as status symbols Fiasco raps,

Now come on everybody, lets make cocaine coolHere Fiasco describes the fabricated nature of the gangsta masculinity particularly how it is constructed on the screen in a music video. He is explicitly challenging the myth of the pop-gangsta rapper whose subjectivity is largely formed by violence, women, and status symbols. Furthermore other artist such as the west coast’s Lil’ B of the California and B.o.B (also Bobby Ray) of Decatur, GA speak to the ways the gangsta masculinity has over-determined their own subjectivities, limiting the ways they expressed their manhood. On Lil’ B’s “B.O.R. (Birth of Rap)” he expresses how enticing the gangsta image was to him, and in this way, begins to interrogate it as the prime masculine subject position: “head fucked up, I thought it would be cool to go to prison/Watching Hot Boyz on BET, getting all these women/ So I got my gold grill because I’m thugged out with’ em”. B.o.B teaks up this same narrative thrust on “Lost Ones”,

We need a few more half-naked women up in the pool

And hold this MAC-10 that’s all covered in jewels

And can you please put your titties closer to the 22s

And where’s the champagne? We need champagne

Now look as hard as you can with this blunt in your hand

And now hold up your chain, slow-motion through the flames

Now cue the smoke machines and the simulated rain

Everything you do from your shades to your shoes

From your chains to your coupe

Came from the tube (read: television)

Trust me I would know

I was raised on it too …

I used to wear a grill

Because it was the trend

Not because I like it

I just wanted to fit in

…

But I was lost

I ain’t know who I was

What else was there to do besides look like a thug

|

| Lupe Fiasco |

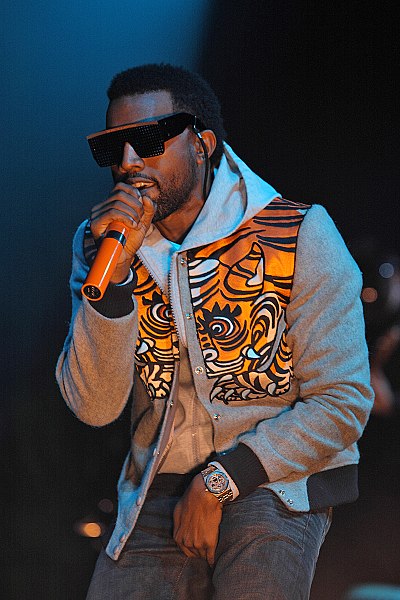

More pointedly many new male artists are calling into question accumulation of wealth as masculine power. Kanye West’s “All Falls Down” engages in a dialogue with the black community regarding consumption culture and its relation to the affects of racism on the black psyche, while also recognizing how black folk are inscribed within a economic system that works against them. He raps,

Man I promise, I’m so self-conscious

That’s why you always see me with at least one of my watches

…

and I spent 400 bucks on this

Just to be like “nigga you ain’t up on this!”

…

We shine because they hate us, floss cause they degrade us

We trying to buy back out 40 acres

And for that paper, look how low we a stoop

Even if you in a Benz, you still a nigga in a coupe

…

Cause hey make us hate ourselves and love they wealth

…

Drug dealer buy Jordans, crackhead buy crack

And a white man get paid off of al of that

…

We all self-conscious I’m just the first to admit it

West directly challenges the material culture within Hip Hop recognizing it in relation to an African American history of oppression and an American ideology that values wealth as masculine power. However, note that West also recognizes that the black body is still undervalued even as it attains wealth associated with masculine power (“Even if your in Benz/ You still a nigga in a coupe”). Throughout the song West recognizes his own culpability in consumption culture and how he uses status symbols to put down other black Americans, a feature very characteristic of late-gangsta rap (50 Cent-“Window Shopper”). Along the same lines Kendrick Lamar’s “Vanity Slave Part I and Part II” also admonishes the growth of consumer culture within the black community and makes explicit connections to the persistence of consumer culture to the lack of power black Americans had during slavery (“So blame it on the 400 years we never saw, the reason why the next 400 we gotta floss”).

Unlike gangsta rappers of the 1990’s emerging artists today are explicit in their conversation regarding the pitfalls of consumer culture within the black community. Opening up this space for dialogue does not of course mean that West and Lamar are not participating in consumer culture. In both songs above the artists are clear about their own culpability within consumer culture, while they criticize its affect and theorize its connections to African enslavement. However, what I am contending here is that their ability to call attention to the fallacy of wealth accumulation as associated with masculine power is a shift from the previous gangsta dominated era.

|

| B.o.B |

Rappers such as J. Cole and Wale occupy female subject positions in order to tell non-conventional rap stories about abortion and prostitution, respectively. J. Cole speaks from both a male and female perspectives on his song “Lost Ones” as he reconstructs a young heterosexual couples argument about an unplanned pregnancy. In the male perspective J. Cole rejects simply leaving his partner to contend with the pregnancy on her own, while also voicing his reservations about their ability to raise a child (“I’m not with them niggas who be knocking girls up and skate out”). From the female perspective, he expresses the anger of a woman who feels that her partner is going to run out on their relationship, and not take any responsibility for the child. In the final verse J. Cole speak from a third perspective and admonishes men who would engage in sex with a women without acknowledging the consequences of a child. The tone of “Lost Ones” moves away from the more confrontational narratives about female and male relationships in gangsta rap. It also calls into question the promiscuous sexual practices associated with the “bad man” and gangsta characters, in which men had sex with women frequently with no regard for the outcome. Similarly, Wale’s “ Family Affair” tells the story of the relationships between a pimp, a female prostitute, and the women’s child. To tell the story Wale takes on the perspectives of all three personas, and through the female’s perspective relates the self-destructive and difficult relationship a prostitute enters with a pimp out of great duress, “Because he kiss every wound that he leaves me/ From the womb, my newborn child/ Although the route’s foul, we need Similac powder” (Similac is a brand of baby food).

Both songs complicate male and female relationships by giving voice to female actors generally left out of masculine rap narratives. Although, female voices in these songs are performed by male rappers; that Wale and J. Cole attempt to inhabit a female subject position is progressive compared to heterosexual black masculinity in gangsta rap that denied space for women’s whole selves. This practice has the affect of decoupling male power from the domination of women, and instead seeks to expose the complications of heterosexual female and male relationships. Unlike the gangsta rap masculine subject position that sought to hide the complicated power dynamics within heterosexual relationships and male anxiety about female sexuality; emerging masculinities seek to expose these anxieties. A masculine identity that is open to dialogue is created as opposed to one that is more concerned with maintaining masculine power.

|

| Kanye West |

Emerging masculinities within Hip Hop are representative of fissures within hegemonic masculinity that allow for challenge to the established norm. However, even as the artists above challenge past assumptions of masculinity, many of them still produce material that subjugates women, and celebrate masculine patriarchal power. Just as their remain artist whose careers are still largely constructed by hegemonic masculinity. The goal here however, was to begin to recognize a shift within mainstream Hip Hop towards a black masculinity that was engaged with the challenges of black men of a new generation of Hip Hop. Challenges to gangsta masculine hegemon are occurring in at least three ways: artist are challenging broadly the gangsta subject position as natural, challenging consumer culture with black masculinity as a point of masculine power, and opening up spaces of dialogue and vulnerability within heterosexual relationships between black men and women. Overall, these fissures offer space for more broad masculine subjectivities to enter into Hip Hop culture.

No comments:

Post a Comment